Our health context is created in part due to our environment, and partly due to our choices. While we cannot control where or to whom we’re born or where we’re raised, along the way opportunities arise to interject and improve overall health in our lives: physically, emotionally, and financially.

For me, my biggest a-ha moment around finances was putting awareness to the many contexts at play: personal, social, and familial, which helped me make informed financial decisions and plans.

As a finance educator, this informs all aspects of my work: intersectionality means awareness of context, after all. Community research, public health, and accessible education are key concepts that can aid in understanding context and developing the crucial awareness we all need.

But first, a bit about why I care…

CLASS STRADDLING

As someone who’s experienced more than one distinct economic reality, am a class straddler, to use Betsy Leondar-Wright’s term, and I celebrate that. I’m white and grew up working poor, in a family that had one parent with an experience of poverty and middle-class aspirations, and one parent with working-class experience and aspirations. Now, I have a middle-class professional job as a technologist.

What I got from my upbringing was a WASP-y sense of reality: no one is handing you anything and everything has its tradeoff bootstrapping beliefs. When we became a one-parent family, we got by for a while on church donations until we moved into public housing. The experience of scarcity doesn’t leave you. But, I’ve learned that I can now choose how I react to it. My new class experience informs my actions, even the ones that were forged from a resource-limited first two decades.

Creatively making possibilities out of economic limitations is what we do when we come from low-income backgrounds. Now, as an artist, I’ve found it really useful to have an open-possibility-DIY attitude. Being a weirdo, a feminist, a lesbian has been easy for me precisely because I didn’t come with any expectations of a middle-class existence to get shattered when I became an underpaid artist or social movement worker, or any parent to let down or fear disownment by—instead, I’ve spent a lot of time figuring out how the heck to have enough (and what that means for me) and how to get around limitations and achieve my goals. My context has meant I’ve needed to understand the difference between external and internal limitations.

Fast forward years and multiple degrees, and I’ve now run my own businesses, contribute to progressive technology, and consult as a financial educator. The context I bring to this work is a crucial element of my success, as is the transparency I share with.

How can we know how to get healthy if we’re not aware of what’s wrong?

How will we know what’s wrong if we don’t know what’s “right”? Intersectional conversations and transparency can guide us, and data can ground the work.

PUBLIC HEALTH & FINANCIAL EDUCATION

A plan for developing financial health can be boiled down to one thing: awareness.

That awareness is strongest when it comes from understanding your personal, social, and your contextual situations together, and here’s where research and data are great allies.

The Population Health Institute at the University of Wisconsin include Social & Economic Factors as well as one’s Physical Environment in their County Health Rankings (CHR)– a well-researched framework of metrics for understanding public health and finding points of intervention at a community level. These two sets of factors account for 50% of their weighted measures, and call out Education, Income, and Employment specifically as indicators of health.

The Center for Financial Services Innovation (CFSI) define Eight Indicators of Financial Health, creating components around spending, saving, borrowing and planning.

Using the CFSI’s framework, one’s personal financial health has points of intervention at what you spend, if you have savings and if your debt is sustainable, and if you have a plan that includes the unknowables of life. These are the points of entry that we can exercise some control over, and which I teach about.

Using the CHR, we can examine public financial health at a macro level. In Brooklyn (Kings County) where I live, 32% of children live below the poverty line and the median income is $51,000. This is as compared to 22% and $60,800 respectively for New York State overall.

These are the intersectional contexts that inform how I teach — and how I’ve come to understand my own financial health.

For me, I knew that education is an indicator of income level, so I got a Master’s degree. I know that my family does not have wealth to pass on to me or to share in an emergency, so I am diligent about saving an emergency fund and for retirement (especially, as a woman I’m expecting to live quite a while more!). I also understand my community context: I’m now more privileged than many in my communities and I understand that means I give back in the form of sustaining donations and to crisis-level crowdsourcing asks.

For my clients and students, I encourage you to ask questions around your context: what is your family situation? Will you inherit, or maybe need to support a parent? What does your access to education and networks of privilege look like? For folks who have recognized your access to resources, what does your situation allow you to do in a community context?

COMMUNITY DATA

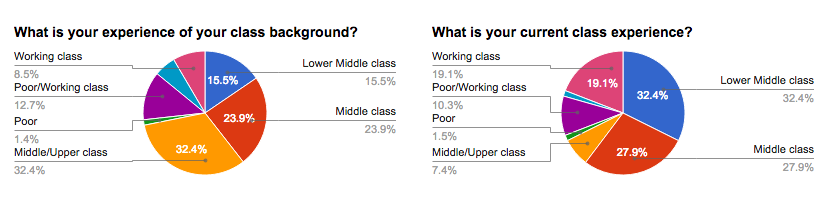

A few months back I began to anonymize, aggregate, and research the set of community data shared with me by my clients: majority LGBTQ people, slight majority of women or feminine-spectrum people, and majority in the 28-40 age range.

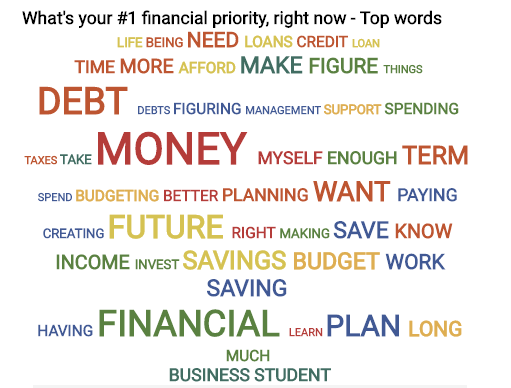

A snapshot of these folks #1 financial priority, right now includes:

I ask my clients a very intentional and specific set of qualitative questions, in part to instigate some thinking about social context and situation as well as personal realities. These include:

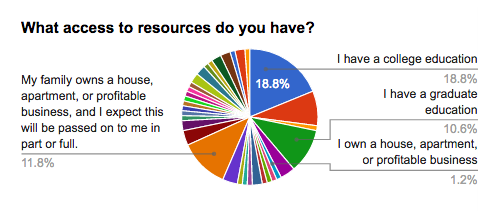

- What access to resources do you have?

- What access to privileges do you have?

A snapshot of these folks self-assessments of privileges and resources looks like this:

Health is a factor of individuals and communities

Public health is a way of describing the health of geographic communities, and is a tool to create understanding social and personal context. It’s part of the story.

For personal finance, defining the difference between old stories, the familiar feeling of defeat, and actual blockades to change is crucial — the difference between “my family never worked out, so I don’t work out,” and going to the gym a few times a week. The difference between “my family doesn’t talk about money, so I don’t talk about money” and getting the information you need to make informed choices about your life.

Finally, as an educator for whom intersectionality and specificity matters, community research can bridge the gaps between fully individualized solutions and macro-level social understanding.

For CFSI’s Financial Health Matters blog tour, I’m happy to share this post. Check out #FinHealthMatters for the whole conversation.

ALSO SEE: Snapshot of you, May 2017

WANT MORE?