Sliding scale is one way that people have come up with to navigate the realities of charging money for things, and for all its challenges it’s a system I use and like a lot.

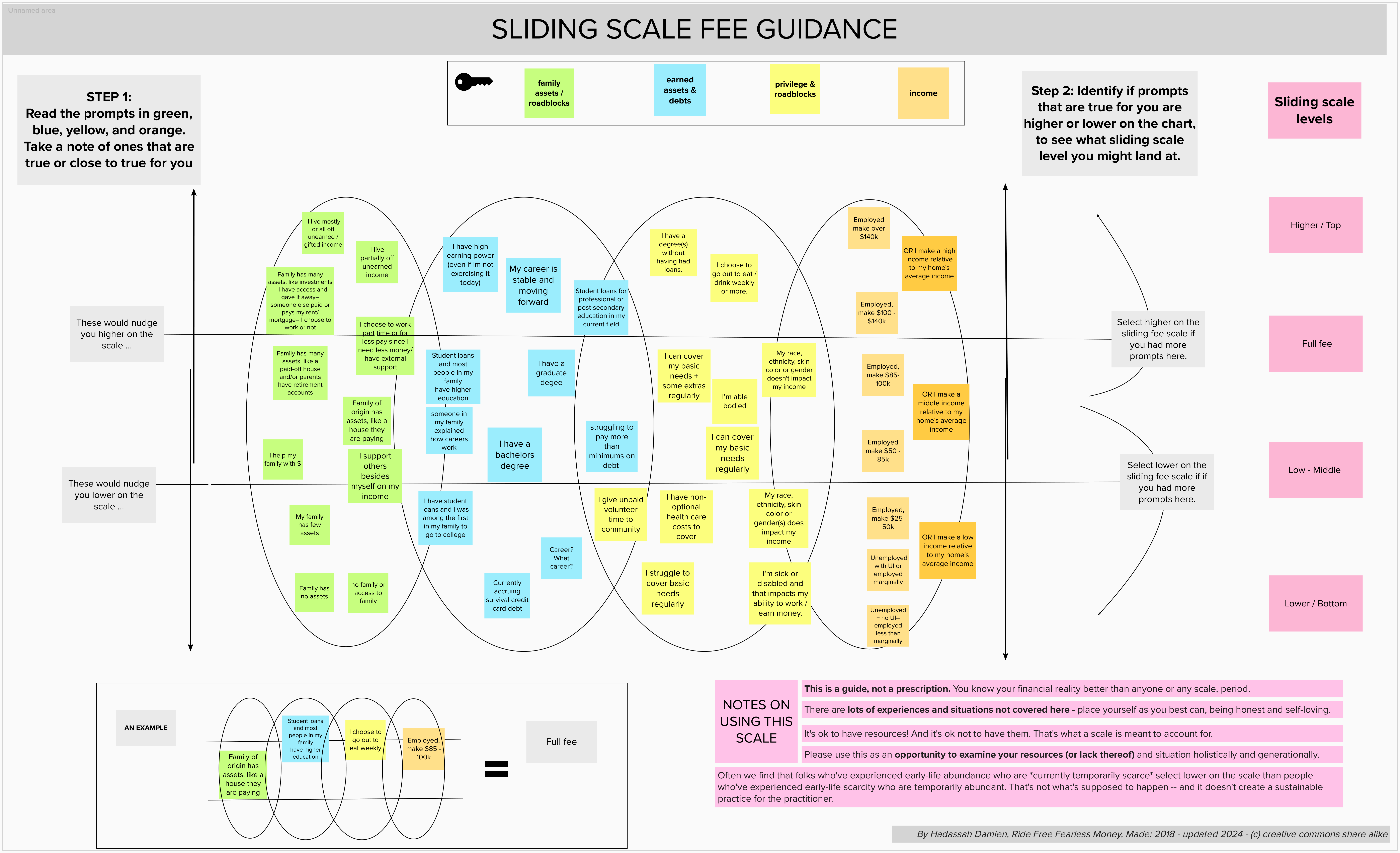

Below is an article about sliding scale, with lots of examples of it in action! I also have a sliding scale worksheet available for free which you can use for your business or collective or whatever, or distribute for free – please cite me, don’t sell it, and download it here:

| Download the English PDF |  |

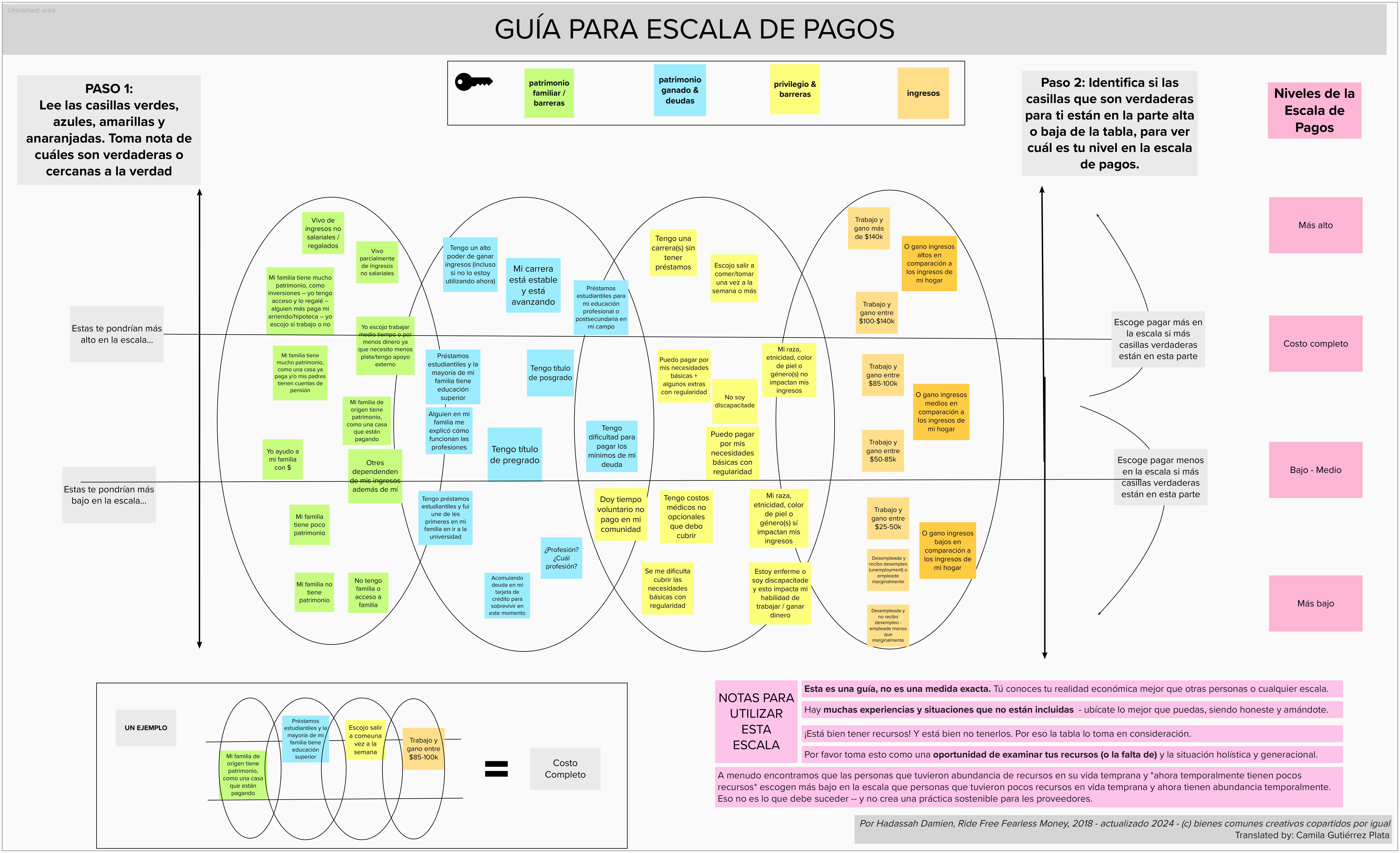

| Descarga el PDF en español – thanks to work donated by Camila Gutiérrez Plata <3 [contact Camila here if you want translation support!] and coordinated by Jo Elliott Gutierrez at Queer Body Collective. Please check out these folks as they did the work to imagine, coordinate, and translate to make this a reality. |  |

The economic concept of sliding scale at its most basic: people pay as they are able to for services, events and items. Those with access to more resources pay more and thus provide the cushion for those with less access to pay less, creating a sustainable economic underpinning for said services, events and items.

Of course, nothing about money is simple, and neither is sliding scale. What feels like “less” to me might feel like “more” to you, after all. After six years of running events based on sliding scale, and the last two years running classes and coaching this way, below I’m sharing some pro-tips, examples of well-done sliding scale models, and give you a few examples of things that went awry so you know what to look out for.

THE DREAM

In an ideal, utopic society, everyone’s natural Marxism comes out and each takes according to her need and gives according to her capacity and everything comes out even. But, we live in colonialist capitalism so it doesn’t play out that way all the time.

CORE PROBLEM

The core challenge is that you get people with more resource access paying less. How does this happen? What’s going on?

I don’t think the problem is that (most) people are genuinely corrupt or greedy – I think the problem is scale, scarcity experience, and comparison. Everyone’s bar is set differently for “enough”.

- Scale: If I’ve never had $100 I don’t already need for something, I’m gonna treat the $20 in my wallet different than if I usually take $200 out of the ATM whenever I need cash to spend on whatever. But if I usually only have $20 and suddenly have an extra $200, I’m also gonna relate to it differently than if it’s a non-event in my wallet. Scale.

- Scarcity experience: Like I talk about here, folks who’ve experienced actual scarcity have a different relationship to what seems like extra money to them than folks who have experienced only the fear of scarcity.

- Comparison: If I’m used to being around broke punks and I have a $40k/yr salary, I might feel freaking loaded. If I’m used to being around lawyers who make $110k/yr, with a $40k salary I’m might see myself as not having much to spare. Or put another way, I might be hella used to living on $2k a month and am willing and feel able to pay in the middle of a scale, but someone who just experienced a wage drop or who watches friends or parents making $80k/yr compared to their $50k might feel like they’re on the “less” end – comparison.

PRO TIP 1

If you’re offering a service or an event and have a baseline amount in mind that is your sustainability cost, make that amount the middle of your scale.

Example: you want to average $10/ticket for an event. Your sliding scale would be $5-$15.

Real-life story: This pro tip is brought to you by my years touring the US doing art that centered poor and working class people as artists and audience. We wanted our shows to be extremely economically accessible AND needed to make sure the touring artists could eat every day. Show after show our badass door babe took copious notes and let us know that we always took in, on average, the middle of the scale. Why? Most people see themselves in the middle. When we realized we weren’t breaking even on tour, all we did to make more money was raise the high end of the scale: $5-20. Now instead of averaging $10, we averaged $15 tickets. It made a difference.

PRO TIP 2

Spelled-out acronyms are part of accessibility. Not everyone knows what MIYHLIYD or PWYC or NOTAFLOF means. Spell it out and level up your inclusion.

- MIYHLIYD – more if you have, less if you don’t

- PWYC – pay what you can

- NOTAFLOF – no one turned away for lack of funds

SLIDING SCALE EXAMPLES

Below are six examples of sliding scale / relational income / class self-assessment tools I think are pretty great (read to the end to see the Worts & Cunningham narrative on “sacrifice versus hardship”, it’s worth it and really helpful.)

I’ve categorized these into a few types: narrative low, narrative range, income-levels, and self-select.

- NARRATIVE – describes who’s “in” for a lower-end scholarship, from the Speculative Literature Foundation

What Do We Mean By Working-Class / Impoverished?

Here are some examples; they are not meant to be comprehensive, but rather to offer some guidelines to help you determine if you might be eligible. We mean to cast a wide net for this grant, so if you think you might be eligible, you probably are. If you have specific questions about your financial situation’s applicability, please don’t hesitate to write to us and ask. You would potentially be eligible for this grant if any of the following apply:

- you’re American, and qualify for the earned income credit,

- you’ve qualified for food stamps and/or Medicaid for a significant period of time,

- you live paycheck to paycheck,

- your parents did not go to college,

- you rely on payday loans,

- your children qualified for free school lunch,

- you’re currently being raised in a single parent household,

- you’re supporting yourself and paying your own way through college,

- you’ve lived at or below 200% of the poverty line for your state for at least one year,

- you’ve experienced stretches of time when food was not readily and easily available.

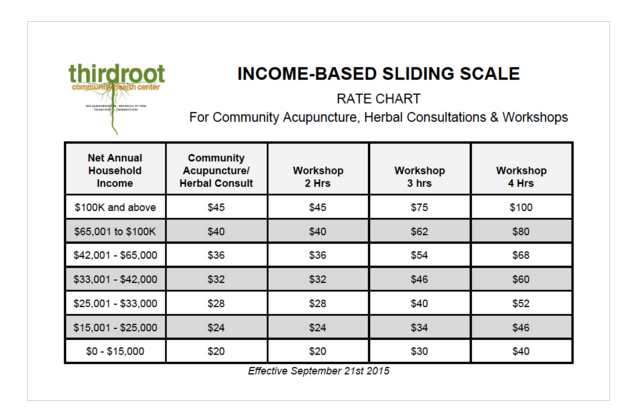

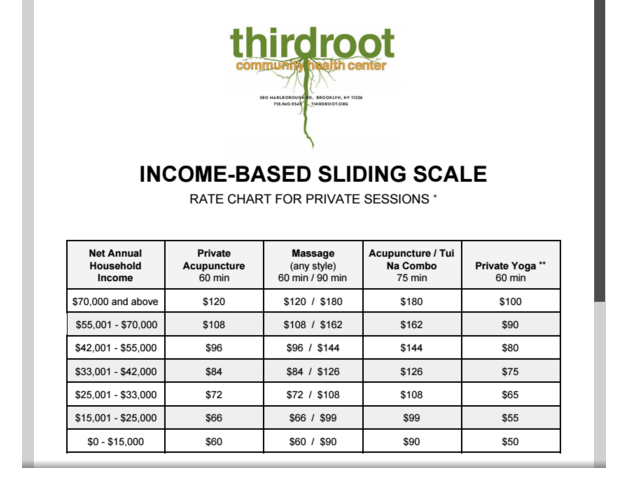

2. INCOME LEVELS – this helpful breakdown is based on NYC incomes that, like many large/expensive cities, are not aligned with the whole US: From Third Root Community Health Center, NYC

An explicit income-level scale functions effectively as a quick-check for people and makes it very clear where you’d fall on the scale.

However, it might miss some of the intricacies of someone’s situation if, say, they make over $70K but are a first-generation college student with a lot of debt who also supports their parent(s). #itsalwayscomplicated

Overall a chart can support people who might otherwise be confused and also helps remind anyone on any part of the scale that there’s a real range of income out there!

3. NARRATIVE – describes who’s “lower” and who’s “higher.” I like giving both ends of the scale a place to be, from Little Red Bird Botanicals (also, cites Underground Alchemy, but the link is broken)

Consider paying less on the scale if you.

- are supporting children or have other dependents

- have significant debt

- have medical expenses not covered by insurance

- receive public assistance

- have immigration-related expenses

- are an elder with limited financial support

- are an unpaid community organizer

- are a returning citizen who has been denied work due to incarceration history

Consider paying more on the scale if you:

- own the home you live in

- have investments, retirement accounts, or inherited money

- travel recreationally

- have access to family money and resources in times of need

- work part time by choice

- have a relatively high degree of earning power due to level of education (or gender and racial privilege, class background, etc.) Even if you are not currently exercising your earning power, I ask you to recognize this as a choice.

The scale is intended to be a map, inviting each of us to take inventory of our financial resources and look deeper at our levels of privilege. It is a way to challenge the classist and capitalist society we live in and work towards economic justice on a local level. While I ask you to take these factors into consideration, please don’t stress about it. Pay what feels right.

4. SELF-SELECT: Just, like, decide based on your gut, from Pronoia Coaching

The Sliding Scale Pricing Model

I am happy to announce that Pronoia Coaching is moving to a sliding scale pricing model. Coaching will now be $60-$140 per session depending on where the client feels they fall on the scale. No questions are asked. Also, I’m aware that $60 per session is still too high for some people; if this is the case for you, please contact me to start a discussion.

A Commitment to Accessibility and Social Justice

Why am I doing this? I know that coaching can be life-transforming work and I feel strongly that it should be accessible to anyone who wants it. As a social justice advocate, I want to do what I can to bring more opportunity to all people. And, personally speaking, anything that broadens the scope of people that I get to know makes my life exponentially better!

My Experience with Sliding Scale Pricing Models

I am part of a spiritual tradition that uses a sliding scale model to price classes and intensives. Sometimes I pay at the top of the scale, usually I pay somewhere in the middle, and occasionally I’ve paid down at the bottom. When I pay more, I know that I am helping others to access the event. When I pay in the middle, I know I am helping the organizers cover costs. And when I pay at the bottom, I know I am letting my community hold me and support me. All of these are wonderful and acceptable ways of participating. I’m revealing my experience with the sliding scale because I want my potential clients to know that I’ve participated at all points and they should feel totally comfortable choosing what feels right for them.

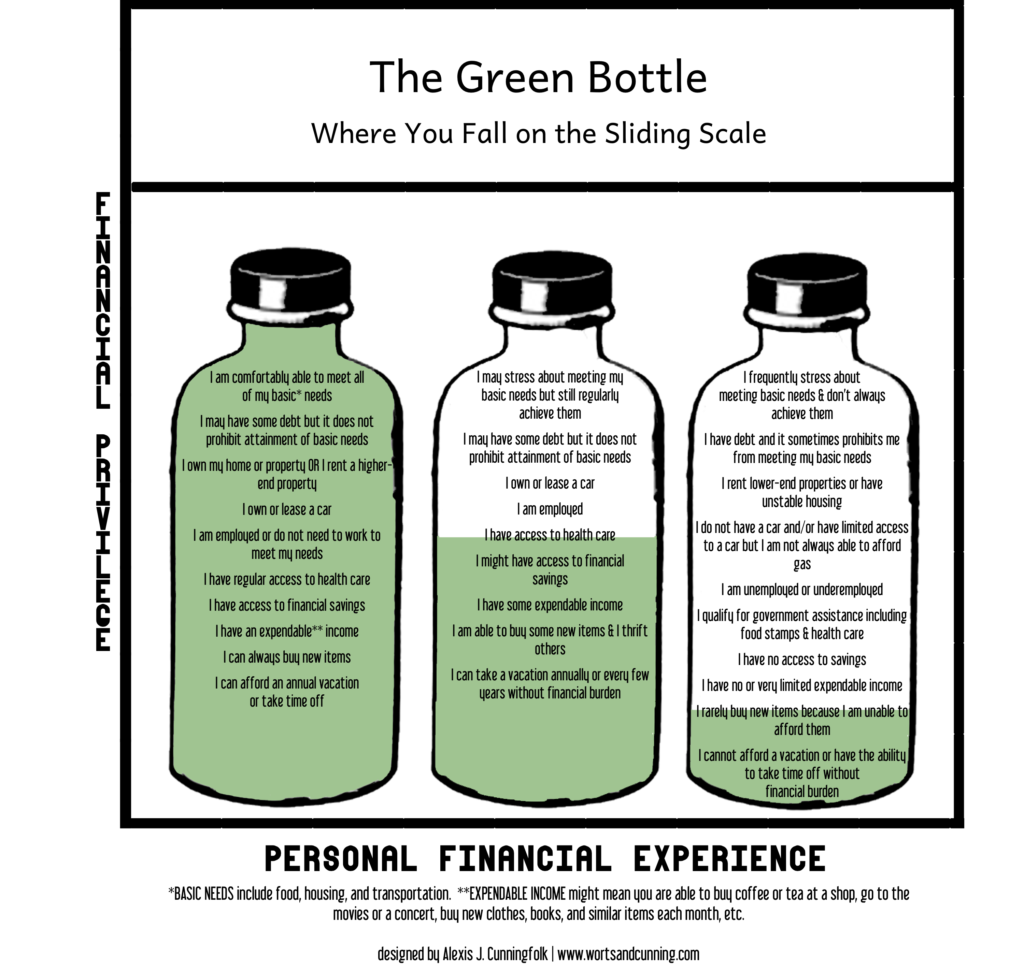

5. NARRATIVE — from Worts and Cunning Apothecary

“Class and economic justice are topics that lots of folks struggle to talk about in the United States because most of us we aren’t educated in schools and the culture at large to talk about money, access to resources, and what class actually is. Class, of course, cannot be understood as an isolated experience, but is part of the complex interactions of race, gender, ability, privilege, sexuality, and the myriad of identities we all hold. I think the sliding scale is a great way to begin a conversation about class because it frames the discussion from the standpoint of access.

“someone shared with me the idea of sacrifice versus hardship when examining access. If paying for a class, product, or service would be difficult, but not detrimental, it qualifies as a sacrifice. You might have to cut back on other spending in your life (such as going out to dinner, buying coffee, or a new outfit), but this will not have a long term harmful impact on your life. It is a sacred sacrifice in order to pursue something you are called to do. If, however, paying for a class, product, or service would lead to a harmful impact on your life, such as not being able to put food on the table, pay rent, or pay for your transportation to get to work, then you are dealing with hardship. Folks coming from a space of hardship typically qualify for the lower end of the sliding scale.“

7. NARRATIVE + GUT + GUIDANCE

Finally , here at Ride Free Fearless Money I use a combination of income guidance like Third Root, and narrative, like Worts & Cunning and Little Red Bird, and go with your gut like Pronoia: check it out here or below, and borrow anything that’s useful to you. 🙂

TWO EXAMPLES OF UNFORTUNATE USES OF SLIDING SCALE

- I worked for a few years managing events for a woman who wanted to implement sliding scale and was, in my opinion, regimented and uptight about it. Just let people be honest and self-select! I thought … until she shared with me a story of a time she’d given another woman who was not working bottom of the scale access to an event – and then the woman cancelled last-minute, saying her husband surprised them with a trip to Bermuda. Frown Face. Turns out the woman wasn’t working because she didn’t want or have to. Not exactly what the scale was intended for even if she technically qualified. Solution from examples above: explicit instructions and demonstrable scales.

- I helped come up with a complex work-trade and scholarship financial access plan for an lgbtq community conference that had a mandate of accessibility in all regards, including economic. We wanted to offer no-cost scholarship options to people as well as work trade in a self-selecting way: applicants would just pick which track would pay their way. Scholarships were given by a different committee, and I led the media work study track. It was a harsh moment when on the first day of the conference I looked over my team, and saw it was all working-class cis people, low-income trans and genderqueer people, and women of color who’d be volunteering alongside me busting their butts. Who was on the very short scholarship list? At least one white person from a well-off background, who was very definitely not working and just enjoying the conference. I needed to know: Why did they apply for the scholarship and not work trade? They were working part-time. I thought a lot about for whom the entitlement to “not work” feels right, for whom a contribution of work “earns” them access, and the difference between working by choice or for survival. To this day I still won’t do work trade: working class and poor people work extra enough already. Solution from examples above: explicit instructions and narrativizing.

In Conclusion

There’s a lot of ways to create economic accessibility with a sliding scale, and just as many ways to engage with it as a user of said scales. If you’re paying on a sliding scale, give mindfully and you can’t go wrong 🙂

If you’ve read all this – you rate really high on my personal sliding scale of committed readers! I hope taking a tour of what’s worked, what people do, and what’s been a mess has helped you think through your sliding scale choices too.

If you enjoyed this post, you might like to:

- Get on my newsletter & get more like this every 2 weeks

- Check out the Quarters Club meet-ups to hang with other like-minded folks

- Read more about sharing money other ways

Youre the best! I was just trying to figure out how to price things on a sliding scale!

This was such an interesting read. I really appreciate how you dig into issues of scarcity and what do we mean by “enough” and how different contexts impact what feels like enough. Thank you for what you say about work trades. That graphic from Worts & Cunning is brilliant.

As someone who’s worked at sliding-scale community acupuncture clinics ($20-$40) since 2010, one of the most interesting parts was reflecting on how many approaches to sliding scale there are, depending on context.

For me and my fellow acupunks, the biggest potential complication with the sliding scale is that someone if someone feels pressured to pay more than is ok for them, that that could be a barrier to them receiving care. We deliberately set the scale so that if everyone pays at the low end, we still make ends meet, and we let our patients know that. Does it help when someone pays more? Of course (no one’s getting rich off affordable acupuncture) but the whole business model is based around avoiding interpersonal pressure as much as possible. Sometimes folks assume that if they identify as middle class then they should be paying the middle of the scale, which would mean $30 per treatment, which could very well mean that they’re only getting poked once a week and not getting enough treatment to feel better. So we do a lot of reassuring to the tune of “NO, really, YOU decide what you can afford, no questions asked.”

Thanks again for writing and sharing this!

I really appreciated this. I’ve done Pay What You Can at shows for years now, and one thing I give a lot of attention to is the language the person at the door is using. This is the script I ask them to use: “Hi! This evening’s show is Pay What You Can, with a suggested ticket price of $20. How much would you like to pay?” I ask them to avoid, especially, using the word “donation” and also to ask people how much they want to pay *before* accepting their money, so someone doesn’t hand over a twenty and then feel shamed/self-conscious about wanting $14 change. This is great thinking on this topic!

Posts/profiles on PWYC and alternative pricing models at http://marketingforhippies.com/category/pwyc/

We have a pretty successful sliding scale herbal clinic at VCIH, but it’s taken awhile (8 yrs) to get here. We have a narrative, suggestive scale, combined with an option to use our local time bank (exchange hours for hours), and the option of receiving a gift (which values the services, while getting them to folks who have neither cash nor labor to offer). I’ll add that when we ran a scale that slid to zero we had far less sustainable income, but bumping the bottom of the scale to just 5 dollars made a significant difference. Thanks for sharing all of this. It’s great to see how everyone handles this topic. To see our take on it, feel free to visit: vtherbcenter.org/community-herbal-clinics/professional-clinic

This is so clear and precise and helpful, thank you.

Thank you for this. I am wrestling with implementing a sliding scale in my solo massage practice (something I’d really love to do)… I’m scraping by and living paycheck to paycheck, but have had family assistance and know I’m coming from a place of privilege. So hard to decide how to implement, as the business owner/practitioner, and in a shared workspace (I can’t leave up signs)! This post has given me lots of thoughts.

I forgot to mention what ever is left in your savings account when you die is required to go to the state! How morbid!

What a great article! It is so wonderful to come across more and more resources talking about sliding scale and economic access to resources. You’ve done such a great job exploring the components behind putting together a sliding scale and dealing with the myriad of perceptions and expectations of the community you’re serving at any given moment. I will be linking back to your work for my readers to learn from.

I especially appreciate your discussion on when the sliding scale does not work. I’ve been working on a follow-up to my sliding scale post about troubleshooting the sliding scale, details on how to talk about and collect money during events in an inclusive way, and why I don’t offer work trade (for the reasons you have already stated – “working class and poor people work extra enough already. ” – damn right). I’m so honored that you featured my graphic and some of my thoughts and especially thrilled to have come across such a vibrant community talking about money and class – thank you, Hadassah!

Such a great overview of an important topic! And thanks for using our sliding scale example. We’re actually discussing refining our process right now to address some issues you mention here, and this is really helpful to see right now. Yay for serendipity, and thanks for your work ?

I love this! So good.