Struggling to understand how to make donations in the context of your income? Wondering if you’re like or unlike others in terms of your giving?

I got you: learn to set clear priorities and giving goals and get the full class context in this excerpt from a chapter on Resilient Giving in this and the next blog post. Or, grab the eBook and read + do worksheets:

Resilient Donations and Giving Plans Guide and Worksheets

Resilient Donations and Giving Plans Guide and Worksheets

Donations are a major way we support and resource the movements that matter to us. Are you donating as much and as often as you intend to? Are you donating the right amount for you?

In this 20-page guide, learn exactly how to:

- Decide how much money is right for you to donate

- Create a giving plan for your time AND your money

- Understand your giving in context with other people's giving habits

- Make sure you are aware of the giving gap - and plan accordingly

Don't wonder IF you're "donating right" -- learn how to decide exactly what is right for you, and make an action plan you can follow today!

Support the orgs you love and change you want to see, sustainably for you. Download this digital guide and start now.

$15.00

Donations are a major way we support and resource the movements that matter to us. Are you donating as much and as often as you intend to? Are you donating the right amount for you?

In this 20-page guide, learn exactly how to:

- Decide how much money is right for you to donate

- Create a giving plan for your time AND your money

- Understand your giving in context with other people's giving habits

- Make sure you are aware of the giving gap - and plan accordingly

Don't wonder IF you're "donating right" -- learn how to decide exactly what is right for you, and make an action plan you can follow today!

Support the orgs you love and change you want to see, sustainably for you. Download this digital guide and start now.

The first time I donated money because I wanted to support something, it felt magnanimous and great. I gave $10 to a friend’s fundraiser. I was living on a shoestring with a hard limit of $30/week in grocery money.

While I’m not sure where that extra $10 came from, since I’m sure it wasn’t “extra” to me, I know I really wanted to help out and so I did. In retrospect, I had the money but didn’t “have the money.” How does donating work in the context of budgets?

Intro

Here, we’re going to explore giving money from a donor point of view. Being able to give money to people, causes and organizations we care about is deeply connecting. It says I See You, I Care, Here’s Some Help. The donations many of us give are a form of us figuring out how to redistribute our resources — any way we share them.

Getting individual donations is a cornerstone of how progressives fund movements. Passing around a $20 bill is how marginalized communities look after each other. Accessing our savings during a crisis is how communities fund rebuilds. Regular giving funds churches and social programs. Grassroots and institutional fundraising efforts depend on people pitching in.

When there’s a crisis, urgency instigates us at a deep level, and giving our resources is a form of care. We know that our charitable giving improves a facet of reality for the recipients. Yet, it can be overwhelming to donate, considering the needs you won’t be able to address; or getting confused by the many options. People get stuck in who and what to give to way more than ever get stuck in the act of giving itself. Additionally, it can be challenging when you’re not sure *if* you have money to share but feel really compelled to do so, and there’s a very real giving gap that’s worth understanding which we’ll explore.

This is focused on folks who earn money, with a few recommendations for people who have inherited money to share. Sure, if it’s not your reality it can be fun to think about how you might hand out money if you were wealthy, but it’s also complex — and realistically most of us figure out how to share and donate money we’ve earned even as we’re managing bills, debt, trying to have a financial future and, oh yeah – getting ourselves some nice things along the way. There’s already help out there for wealth-based donations, here’s a resource to help earners plan giving.

In this excerpt you’re going to learn a step-by-step method to identify an amount of money you can donate and a plan to move it regularly. You’ll also learn a way to honor the time you donate, and a framework to make a whole plan so you’re getting it done and not overthinking it. Ready?

Naw, just tell me: what’s a person committed to sharing their money to do?

Want the easy answer? TLDR; Donate some of your time and around 5% of your money after your expenses are covered (more if you have high income) to things that matter to you.

Now, if only understanding context and actually sharing your resources was actually that simple.

If you’ve ever stopped to check your balance before clicking Contribute on a campaign, or doubted that your $10 mattered (it has!), this article is for you. This is also definitely for folks who find themselves with wealth to share; I know you often end up pausing in a sea of good options because time itself is a limitation — a giving plan in place helps overcome that block so you can do what you mean to and give your money where it’s needed.

What is a giving plan & Why would I have one?

A Giving Plan lays out how and to what you’ll give money away (sorry to be so basic but there you go). The *plan* part here is the major differentiator from … just … like… giving whenever. People go about charitable giving and donations in various ways I’ll break out later on. Your plan should be clear enough that you can just follow it without having to do guesswork. The whole thing should make it easy to donate!

A giving plan is a way to make contributing money or other resources easier. It’s about putting guides in place for yourself to come up with: how much to give, when you give, and how you give. Figuring out to whom or what to give money — and *actually doing it* is now easier because you don’t have to stop and say, “Do I have the money?” This, friends, is a Giving Plan — and they’re not just for people with wealth. We all can put a Giving Plan in place to take some of the work out of sharing our resources and to stop and honor what we’re already doing.

You have a giving plan to simplify things.

With a plan, you don’t have to spend tons of time thinking about the logistics of giving money — you just get it done. Like so many other parts of money and resource management, it’s less about the money (or volume of money) and more about setting yourself up with a structure so you can do all your other, non-money things with less background noise, executive function drain, and stress.

One important addition we include is your volunteer hours, community work, and time spent supporting people who are “doing the work” — not so you share less money, but so you get a full and accurate sense of what you’re giving. Reporting on charitable giving never accounts for this!

Below, we’ll unpack the pieces of a giving plan and then look at some sample ones. But first, let’s look at a funny thing that happens, as always, somewhere between the economic bottom and top incomes when it comes to giving money. From that, we’ll get to building your plan.

Understanding Giving and Your Income Level

Scale matters, and I want to make room for you with the limited time and money as well as you with the spacious bank account or calendar. If you’re scraping by or constantly working, you probably have less wiggle room than if you have actual excess income.

But if you’re struggling, we know that doesn’t mean you don’t give. As a matter of fact, a recent report noticed that people in lower income levels tend to give more, and more often – and that giving for lower-income people is tied to empathy while giving in higher-income people is tied to individual accomplishment. Hmmm.

Sometimes, we give money that we “don’t have.”

Looking back, when I gave that $10, I pulled it away from other things I needed – deep giving out of a shallow pocket. Frankly, lots of money gets passed around this way. My friends and I call it the Queer $20 that we just keep circulating from fundraiser to crowdsourcer. A $25 gift from someone making $250/week is 10% of their weekly money, meaning it’s way more of a bite than a $25 gift of someone making $250/day (for whom it’s 2%).

This is exactly why $10 (and $5) contributions mean a LOT. They tend to come from people who freakin want that thing to have their darn money cuz it matters that much to them.

Here’s a key takeaway: When we have less, we tend to give more, as relative to our assets.

Even typing this seems like basic knowledge: when we are connected to the experience of needing things we can’t pay for, we more readily understand what it’s like for others to need things and have no way to get them. The psychology of access is fascinating, though this statistic also bums me out. Folks in the middle, who have more resources than low-income folks, but way less than, say their boss or media wealth examples, are stuck without a compass to indicate where enough is. We’re about to see how that plays out in giving patterns.

HACK: Take time to really understand the reality of other people’s lives. Think about how $20 has meant different things to you at different times, and generate a respect for how people with less resources make their money work wonders. #shoutoutsinglemoms

So donating is just relative to income?

Much like sliding scale, a giving plan will usually change in relation to your access to extra money AND your sense of need AND scale.

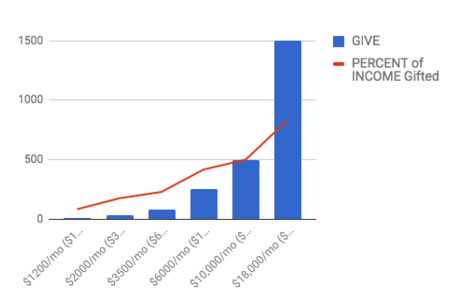

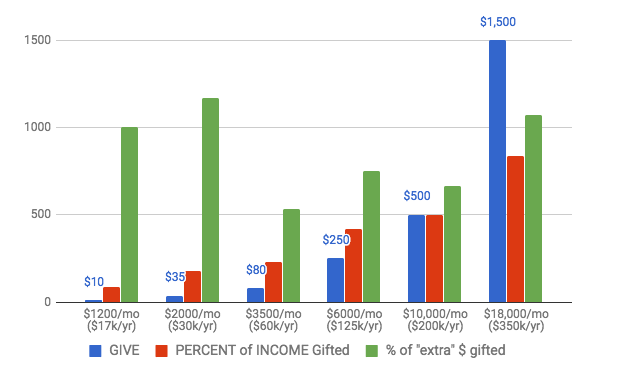

The chart example goes from someone making $1200/mo giving $10, to someone making $18,000 giving $1,500, and we see an asymptotic curve to the increase in giving (oohhh math words) which just means having more money = exponentially more giving. There’s literally more wiggle room to give from →

Ah, people with more money overall give increasingly large amounts?

Yes and no. Once you have a certain base amount of money all your needs are covered (that estimate, by the way, is $75k/year salary). Once you’re covered, you’re not making a deep pull from a shallow pocket, but instead a deep pull from a deep pocket. The pocket is still deep after.

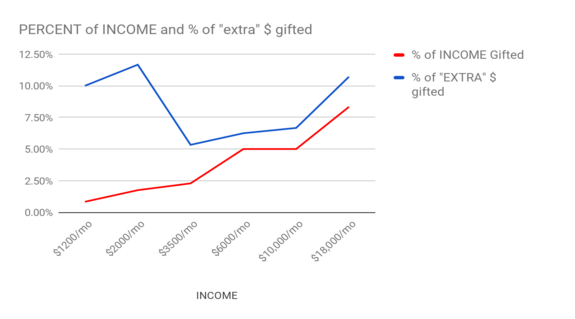

At ends of the income spectrum, giving *as a percentage of income* is higher than in the middle income. It looks like this:

The part in the middle is where I bet a lot of you reading this are in terms of your income. Breaking down the numbers gets us to a factor that is intersectional and worth poking at more. Look again in the middle of the chart, at giving at $2,000 month, versus giving at $3,500 or $6,000.

There’s a dip in the middle of giving when we examine our finances after costs, where there is a curve upwards when we only look at income.

There’s a giving gap here. What’s it about?

For all of us, some of our money has to go to pay for crucial shit, and some amount — maybe small, sometimes large — of money is left for everything else. I have a hunch, and it goes like this: when you’re broke, you’re not even trying to pay for non-urgent things like, say, a crown – so what’s $10 to a fellow person in the struggle? Take it.

But once a little bit more money comes into play, that’s when the hope of getting these needed things hits – and it’s pricey. #retirement #thatdentalworkyouputoff #niceshoes #gettinghitup

These are the numbers charted, and they calculate after accounting for covering your crucial survival needs as well as money that’s about your oxygen mask and goals. So, say each month:

- You have $100 left over, giving $10 = 10% of your money.

- You have $300 left, so $35 = 11% of your money.

- You have $1,500 left, so $80 = 5% of your money.

- You have $4,000 left so $250 = 6% of your money.

- you have $7,500 left, giving $500 = 7% of your money.

- You have $14,000 left, giving $1,500 = 11% of your money.

The chart below shows this information another way. The green bar represents the percent of someone’s after-tax income, after costs are covered, that might be true in a typical scenario:

I want us to acknowledge that giving $10 when you have $100 for your needs is as generous as a $1500 give from someone making $350k a year who has $14,000 a month to play with. I also want us to acknowledge the generosity gap in the middle incomes, not to shame anyone but just to know that it’s common, happening, and we want to make sure we give so we don’t exacerbate it..

Your Key Takeaway:

It’s not ultimately about standardizing a 10% or 5% donation — you’ll get to your personal donation baseline in the next section. It’s about: understanding what you have available to give from, and that there’s a squeeze on a LOT of people that plays out differently across class.

Your Giving Plan First Step: Know Thy Money!!

Ok, we’re informed and ready to get GOING. Where I think it’s intersectional, strategic, and wise to start making your plan is: first, understand the money you have left over after your most important costs are covered to inform your giving plan.

Your equation: (total income) – (how much you *have* to spend monthly to survive) – (long-term needs/goals) = everything left for planned donations and entertainment/consumer spending.

You need to know what your basic life costs are. Yup.

I don’t mean the fun stuff: I mean the CRUCIAL stuff. A review of your bank account and credit cards will reveal these “hard costs,” the money you have to spend or else there’s a problem, like rent/mortgage, insurance, debt minimums, and utilities. As well, buried among your spending are the moving pieces of your mutable spending. (ps. here’s a workbook to help you sort this if needed)

Finally, there’s your goals and future self money that we should think of as important enough to get their own category. What are these other kinds of costs that you should bring in? It’s intersectional, folks.

For example:

- If you’re a first-generation college student trying to get up so your family has someone with resources, you may have lotsa student loans or money you need to send home

- If you’re a single, unsupported parent you may have extra costs for your lil one(s) – hell, having kids when you DO have resources might mean you want to save for their college

- If you’re from a poor or working-class background, you may want to save more for emergencies as well as retirement since you have no expectation of inheritance or a financial safety net

- If you’re dealing with health issues, you may have extra wellness and care costs that insurance doesn’t cover

A note on class and future self money: If you’re from a background where, like about 20% of Americans, you think you’ll inherit a decent amount of money from a parent or grandparent, putting money into retirement and savings are still VERY important, but the crucial level you need can be less than other people. Let that sink in, and apply as needed when you’re calculating your crucial future savings.

Ok – you’re going to look at your money to understand:

- What comes in

- What you HAVE to spend to be housed, fed, and pay minimums

- What you NEED to hold back to put the oxygen mask on yourself

- … and then, you’ll have a number. As long as it’s not negative, that’s your “extra” — the money you have to work with in your giving plan and which covers everything else: clothes, food, entertainment, cable, subscriptions, electronics, travel.

Great – I have a number! What besides plans for donated money can go in my giving plan?

Your “other giving”… account for it.

Do you send money to family, or participate in tithe or similar community resource support?

Please, add it into your plan. First, so you have planned for it. Secondarily, so you recognize your contributions as part of the large support systems needed to keep social fabrics intact.

Your time.

Other valuable resources you have include: YOUR time! Your energy! Your care work! Your emotional labor! Your dinner cooking! Your phone calls!

When we talk about sharing resources, usually the focus is on money as the core resource.

However, money is always a proxy for things we need, and tends to stand in for accessing things via purchase: buying food, buying clothes, buying office supplies, buying rent for a meeting space, buying the time of those who staff the organizations that do the work.

There it is: our donations, reasonably, often partially help pay workers’ salaries. This is a good thing, as workers supporting communities, grassroots campaigns, and social good organizations deserve fair wages and access to resources themselves.

For many of us, part of how we participate in our communities, movements, and support in crisis is with our time: volunteered formally when you show up at a meeting to help, or informally when you cook dinner or get on the phone for support workers after their “real” work is done. This support labor, as well as on-the-ground volunteering is another donation of your time resources.

What forms does this labor take? An incomplete list includes:

- participate in a meeting, assembly, march, hackathon, organizing, emailing…

- work as part of a collective, unpaid community group, or volunteering…

- care work, in the forms like cooking dinner, emotional support, giving friends rides, coordinating legal aid or physical donations …

I advocate that we include time donated in our giving plans: in part to help us understand what’s *really* going on, and in part as a reminder to honor unpaid labor as labor.

In the giving plan in the next excerpt, I suggest and assume a $15/hr rate of pay for time for all people. You might make more or less than this rate, but using it as a baseline means we’re equalizing labor value without inflating certain kinds of work. If that makes no freakin’ sense to you, as you’re making your giving plan then by all means change the hourly rate or don’t include your time.

Loving it? Learning?

Read on to part 2 of the excerpt to see other people’s giving plans, or download the whole chapter + a donation calculator below.

Finally, a big THANK YOU to Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha for her comments on the draft regarding including emotional labor in our giving, and to Ariel Speedwagon for the term “Giving Gap” and donor research support.

One thought on “Resilient Giving Plans: get ready to donate and mind the giving gap”

Comments are closed.